Musical biopics seem to follow a set formula. They begin with scenes of a famous musician as a child and portray his or her domestic struggles: a negligent parent, an impoverished home, a battle with depression, or some combination of the above. As a young adult, the artist finds an outlet through music and becomes an early success until the demands of the music industry stir up a new pot of troubles: drug addiction, damaging relationships, and intrusive media attention. These story lines, as dramatic as they are, have made the biopic genre predictable. Because the narrative structure offers little surprise, biopics end up resting on the strength of their main performer: Angela Bassett, Jamie Foxx, and Joaquin Phoenix to cite a few.

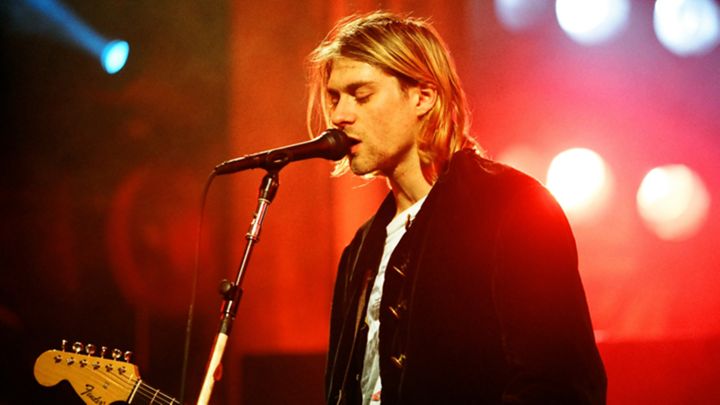

Music documentaries, by contrast, portray those stories with a clearer lens. Relying on real footage, documentaries render the narrative as complex whereas the biopic counterpart portrays it as melodramatic. Two documentaries have recently emerged that illuminate the rise and fall of music artists: “Montage of Heck” about the life of Kurt Cobain, and “Amy” about Amy Winehouse.

The revelatory and brilliantly edited “Montage of Heck” depicts Nirvana’s transformation from a punkish trio playing dive bars to an artistic force nearly synonymous with 90s rock. The atonal chords and drum smashing of the band’s early years evolved into a more focused and melodic expression of angst, drawing a template for grunge music.

Nirvana’s trajectory impacts everything in the film, but its central focus is the life of its front man, Kurt Cobain. Using footage released by Frances Bean, Cobain’s daughter, the documentary begins with home videos of Kurt and his parents. Director Brett Morgan goes in deep on Cobain’s early signs of depression, his parents’ disdain, and his first experiences with drug use, delving into Cobain’s psyche and literally onto the pages of his adolescent journals. Morgan displays the journal entries as written in real time as though we were peering over Cobain’s shoulder as he wrote each line.

In his teenage years, Cobain quit school and spent his time working as a janitor and listening to punk music. Feeling increasingly depressed, he made an attempt at suicide by lying down on neighborhood train tracks, a plan that was narrowly avoided when the train made a last minute track change. He looked to music for emotional expression and found a natural penchant for song writing, jotting lyrics on notebook paper and dedicating himself to daily practicing.

During his time he lived with a girlfriend who supported him, though both were poor and, without any sort of medical coverage, Cobain began using heroin as a remedy for pain relief. Even as his wealth increased in the following years, Cobain continued to live in a way that could be described as penurious. As Nirvana amassed a sizable following, Cobain balked at the idea that his music was in any way a commodity for consumers. He hated giving interviews, hated media attention, and hated journalists imposing their perspective on what his songs meant. His passion for connecting with audiences never meshed with the other side of the business – the cameras, the magazine covers, and the implication that his art could be package and purchased. While many journalists wrote about Nirvana with sincere admiration, Cobain seemed to feel that the press would intellectualize music rather than experience it viscerally.

Beyond wealth and fame, Cobain felt the encumbrance of the media’s probing lens into his family life. The most damaging example was a Rolling Stone article by Lynn Hirschberg about Cobain and Courtney Love’s heroin use during Love’s pregnancy with their daughter. The article was not without validity – Love admits in the documentary that she used heroin while pregnant – but the fallout was humiliating. Child services took Frances out of her parents’ custody for the first weeks of her life and Cobain’s depression increased irrevocably. His anger is heavily documented in his journals, and it's worth noting the absence of technology in Cobain's life. The Internet was not yet commonplace. Cobain’s entire creative and emotional world existed onstage and in the pages of spiral notebooks.

Throughout the film, Nirvana’s music permeates, often with new takes on familiar songs like a calm, almost choral version of “Smells Like Teen Spirit”. There’s a haunting quality to the film and to the reams of journal entries revealed. For Cobain, success could never numb the sting of feeling critiqued, interpreted, and probed. The media and the naysayers were relentless, he thought, drawing blood and seeming to exclaim, in Nirvana’s words, “Here we are now, entertain us.”

Why are we fascinated by the famous artist who wishes to be left alone? Just as there was no incongruity for Cobain in wanting to connect to huge audiences onstage yet avoid conversation offstage, there was no disconnect for the singer Amy Winehouse between performing songs that laid bare a painful relationship and wanting to shrink from visibility after each show.

Like “Montage of Heck”, the beautiful and disturbing documentary “Amy” implicates the public and the media in the self-sabotaging behavior of a talented but fragile artist. Another prodigious song writer who struggled with addiction and died at age 27, Winehouse attempted several times to rehabilitate but was subverted at every turn by the two people she looked to for guidance: her father and her husband.

Winehouse’s musical gifts were obvious at an early age. The film’s opening scene shows an adolescent Amy singing “happy birthday” with the vibrato and stylings of a seasoned performer. As a young teen, she was eager to learn from the great jazz artists, particularly Tony Bennett. She was initially a jazz singer herself and with barely any training showcased the voice and timbre of a singer three times her age.

Like other performers before and since, Winehouse was marketed as a mainstream pop singer though her sound and musical preference were better suited for smaller venues. The frenetic schedule and stadium performances exacerbated her drug use, leaving her with few healing mechanisms.

Winehouse confesses in the film to a history of depression and bulimia. Her father’s extramarital affair and divorce from her mother shook her as a teenager and made her “messed up” about men, even as she continued to look to her father for reinforcement and approval. In video clips with friends, however, her demeanor is charming, upbeat, silly, and playful. Unlike Cobain, she had a circle of good friends. But her father and Blake loomed larger than anyone. Their names are literally imprinted on her: “Blake” just above her heart, and “Daddy’s girl” on her upper arm.

One is reminded quickly that Blake – a club boy in fedoras and cuffed t-shirts – is a toxic waste dump of a partner who brought heroin to the hospital where Winehouse was detoxing from a drug binge. Most of Winehouse’s album “Back to Black” is about him, primarily her heartache and loneliness in the months after he left her. Her biggest single on the album, “Rehab”, was a nod to her friend (and former manager) Nick’s effort to help her rehabilitate and her father’s dismissal of the intervention. Listening to the lyrics again, the line, “My daddy thinks I’m fine” stands out as heartbreaking. Her father was blind to her wellbeing so Winehouse assured herself that rehab was unnecessary.

“Back to Black” became the tipping point for Winehouse’s career, hurling her faster toward international tours and arena-sized concerts. The grueling schedule – promoted by her father and her profit-hungry manager – escalated at the same time that Blake came back to her, bringing his drug addiction and co-dependency habits back into her life. Against all powers of reason, she married him, and in short time he was arrested for drug possession. After that, Winehouse signed a written agreement to get clean by that year’s Grammy awards. She followed through and scooped up multiple Grammy awards entering a healthy period of musical collaboration with artists like Mos Def, Questlove, and her idol, Tony Bennett. But this upswing came too late, her body already pillaged by the long-term effects of substance abuse. She died in 2011 of alcohol poisoning.

A highlight of “Amy” is seeing her song lyrics superimposed on footage of her performances. Winehouse’s voice is so striking, you almost miss how clever and poetic her lyrics are. Her writing is filled with word play, metaphors, and tactile language alongside stark descriptions of loss and loneliness. From “Wake up alone”:

This face in my dreams seizes my guts

He floods me with dread

Soaked in soul

He swims in my eyes by the bed

Singing was never leisurely for Winehouse; there was a visceral need to unleash the words. One of the most profound moments in the film is Tony Bennett’s expression of praise that she ought to be named among the great jazz talents like Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. What pains is the notion that her image as a drug addict eclipsed that public perception.

The prevailing idea in both “Montage of Heck” and “Amy” is that fame hurts. It damages, corrupts, and interferes. Musicians thrive on live performance and audience connection, but we shouldn’t assume that because we memorize their lyrics, we know them. They don’t owe us anything and they never did.

photo credit: Jeff Kravitz, Dan Kitwood