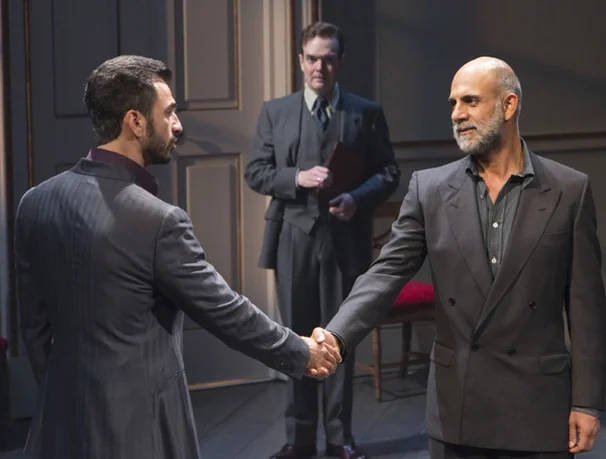

I first encountered the script for Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer-winning play Disgraced in the pages of American Theatre magazine. I was amazed by the writing: tight and structured yet incendiary and thought-provoking in every line of dialogue. In each subsequent encounter with his work – his novel American Dervish; his play The Who and The What (which ran at Lincoln Center Theatre in the spring of 2014; the Broadway production of Disgraced; and most recently the New York Theatre Workshop run of his latest play The Invisible Hand – I’ve been continually impressed by his exploration of identity, religion, and culture – both Muslim and American.

In an article for The Jewish Week, I wrote about the illuminating Jewish characters that surprisingly appear in Ahktar’s stories, as well as the myriad influences on his work. Below are excerpts from our conversation.

When I walked out of The Who and the What this spring, I remember feeling very grateful that there’s a playwright who can write about religious people without shrinking them. I’ve seen versions of Afzal [the Muslim father in the play] within my own community. He was very recognizable.

Tevye.

Well, right. That’s the quintessential Jewish parent figure in theater.

There’s a quote from William Faulker that writers often reference: to write, you need experience, observation, and imagination, but sometimes one can take the place of the others. How do you think those three are comprised in your work?

The characters in my work are taken from the observation of life and experience, I mean, certainly American Dervish is a version of my family. But I also want to tell a good story. How I draw from observation and experience has to do with what I want to do imaginatively. What I’m interested in is the movement from one point to another and the recognitions that happen along that path. That, to me, is the definition of drama. So what that requires are strong events, sometimes stronger than actually happen in life.

It’s also very clear that structure is at work.

With Disgraced, I can tell you that’s what I was thinking about. I don’t know that it comes anywhere close, but I’m gonna make a comparison to Oedipus Rex, which is the purest dramatic structure there is. I don’t think Disgraced has that, but it’s trying to get there. Now we think of tragedy [in drama] as an enobling form whereas I think for the Greeks it was more of a visceral form. At Disgraced, the audience is very vocal, and that sense of participation is important to the physical experience that the audience is having.

The night that I saw it, it almost seemed at the curtain call that the audience was clapping in slow motion, like they were physically still in the play. There’s so much packed into the show that it’s almost impossible to process it all upon leaving the theater.

Yeah, [they’re thinking] “What was that? That was a ride into a concrete median.” (laughs)

I’m interested in how you first came across Jewish writers. I know your work has been impacted by them.

I had a middle school teacher and she gave us a [reading] list, and I for whatever reason chose The Chosen. I was enraptured. I felt like I had found my own people. They had all the same divisions in the community and the concerns with being holy and being righteous, and how that brought people into conflict and how it brought them happiness. I even got the texture of their life. And this is about Chasidic Jews in Brooklyn, not about a suburban kid in Milwaukee [where Akhtar grew up]. But somehow it was very familiar.

Then I read The Promise and My Name is Asher Lev. [Potok] was the first writer I read all his books. I remember reading My Name is Asher Lev and getting to the end where [Asher] walks out of the gallery, and I thought, “This is my life.” I think I had some innate sense even before I even had a thought that I would become an artist that there was this division between the old world and my own life that that was irreconcilable and it was headed for some kind of rupture.

Even though your parents were not active Mosque-goers.

My mom was devotional without being rigid about it. My dad became militantly…he’s basically like Amir [in Disgraced] now. He didn’t become that way until I got to college. Before that, he was more tolerant of it. But my mother’s sister was particularly devout and I had a close relationship with her. And I spent a lot of time around extended family, all of whom had varying gradations with identification with being good Muslims. That was one of the central questions of my childhood: how to be a good Muslim.

I college, I can’t remember how I came across Saul Bellow and Philip Roth, but it was the same sense of recognition in a different way. It was the refined literary me having the experience I had with Chaim Potok. And then the real experience in college was Woody Allen. Everything from “Love and Death” to “Husbands and Wives”.

Why do you think there’s so little in theater about religion? Is it as simple as audiences tend to be irreligious?

Well, maybe. I think the prevailing dramaturgical paradigms privilege certain subject matter. Directness is not as valued, and earnestness is not as valued. And issues of faith require earnest, direct technique. Because if you want to write about it, you have to find a different Archimedean point than ironic detachment.

I think that faith is one of the important themes in American life, but it’s hard to find major writers writing about it. I mean even Chaim Potok – people do not speak of him in the same breath as the Roths and the Bellows. And Roth has made a career of writing in opposition to faith.

The character Isaac in Disgraced feels accessible to secular Jews – he intermarries, he eats pork – but he still seems to feel a personal attack when he’s called out as being a Jew. So there’s something visceral there. Nathan in American Dervish does as well, though he’s very willing to convert to Islam, something Jewish audiences might find less relatable.

There was a template for Nathan in my own life. It’s a very odd situation for a Muslim artist to have found most of his inspiration and his roadmap from Jewish American artists. I’m always grappling with that conundrum. It’s a different kind of anxiety of influence. How much of this is really mine and how much is not mine, and how much of it can I make mine. So I think Nathan is the first fully fleshed-out attempt at that kind of internal dialogue. There will ideally, hopefully, be a sequel to American Dervish that will develop this further: Hayat [the story’s main character] will find his way back to Islam by working with a Kabbalistic master. So it’s this circuitous route.

Islam is really a gloss on Judaism. The Quran is in many ways a secondary source commenting on the Old Testament and then reworking sections. So when you look at it from the point of view of Harold Bloom, for example, we’re talking about Mohammed’s anxiety of influence with regard to Moses. And to make himself into a better Moses.

While the The Invisible Hand and your 2005 film “The War Within” are about terrorists plots, most of your recent work – Disgraced, The Who and the What, and American Dervish – offer very different critiques of Islam, based more on the text of the Quran.

All three are challenges to Quranic interpretation.

And people have asked you in interviews if you’re concerned about reflecting a negative image of Islam. But the characters in most of your work are not talking about extremism or terrorism, per se. They just don’t want to feel diminished by religion.

I feel that Amir is grappling fundamentally with how to fit in. The idea that W.E.B. Du Bois has about double consciousness: the view a minority has of the majority’s perspective on it. I think that people expect me to be writing more from a place of double consciousness than I am. I don’t suffer from double consciousness. My experience is my experience…and I just write from that place. And then I find myself in this peculiar situation where people are reading my work and looking for clues to the quandary of double consciousness which is not present in American Dervish at all. It is there is Disgraced but in an unusual way because it’s not like I’m siding with Amir over the other characters.

Do you wonder how many people leave the theater after Disgraced ends and say, “So, is he saying that Islam is bad?”

I think it’s an invariable question. If you really sit with the experience you have, I don’t know how you can take Amir’s side and discount everything that has made you complicit with his downfall if you’re not Muslim. It feels like a sledgehammer but I think there’s a lot of subtlety there.

If Amir had been upfront with his colleagues early on, would it have mattered that he was Muslim? I don’t imagine that it would have.

Yeah, it might not have. And that’s another dilemma. The concern that internal paranoia within the Muslim community might be exacerbating the situation.

What is your feeling about Muslim Americans who are outspoken advocates, like Reza Aslan who is a frequent commentator on CNN?

That’s part of our cultural consciousness – that constant chatter, so if there isn’t somebody representing that pole... But I don’t feel that that’s an artistic project, it’s a public relations project. So a lot of people might think, “I heard about this guy with a weird name who won a Pulitzer. He’s into Muslim stuff. I guess we’ll find out that Muslims are good people.” That somehow an artistic project will modify in a positive way what they think. So, I love Reza, but that’s a different thing.

Amir and Abe are complex and troubled Muslim characters, certainly more so than Hayat and Mina [characters from American Dervish] and the family in The Who and the What who are more lovable characters.

Somebody once told me, “I think your play is a litmus test. It’s telling an audience member where they are on the spectrum of their own tribal identifications.” I think that’s true. I don’t know that I have a message. I think there are certain meanings that are embedded in the text, but I don’t think you can come away thinking anything specific other than an interrogation of your own relationship to tribalism.

As a final question, I’m curious about the character of Emily, specifically her last lines. Was her interest in Islamic art truly sincere, or was it an outgrowth of being married to someone Muslim and wanting to find beauty in his culture? It seemed to raise a larger theme of being fascinated with cultures outside of your own experience, like the way you illuminate Jewish characters. Like Gershwin doing Porgy and Bess. What is your thought about portraying subject matter outside of your experience?

I think Emily’s last lines express the Western, non-Muslim frustration with the Muslim world which is something that you only see growing, tragically. That even those who wish to find meaning and beauty are having difficulty today. Emily compassionately walks away. The second part of your question is beautiful, I don’t know that I have an answer to it. I think I’m very conscious of the ways in which I can write about things that are not my experience or my place to write about. I’m sensitive to the boundaries. If I feel confident I’ll write about it. I also show my writing to a lot of people, so I get a lot of feedback.

It seems like you’re an avid rewriter.

I am. The inspiration comes in rewriting.

photo credit: Nina Subin